Thing-ing the Internet with Songcamp

In 2021, the concept of a web3 record label was buzzing. The cool kids were all over that idea. You might guess that Matthew Chaim, a musician who'd begun delving into the crypto sphere, would share their enthusiasm. But he felt ambivalent about the prospect.

At the risk of sounding trite, record labels are The Man. They turn music into a corporate product. Matthew was not totally unwilling to shake hands with The Man, when it seemed worthwhile — he had signed his own record deal, once upon a time.

But when covid hit, Matthew packed up to leave Los Angeles, philosophically as well as physically. He returned to his hometown of Montreal. A year later, he was not eager to recreate his music industry experiences. A web3 record label "didn't feel like the new evolutionary or transcendent thing," Matthew explained to Splits. He wanted to explore a fresh landscape.

Crypto was exciting because the power structures were all topsy-turvy, constantly shifting, like the view through a kaleidoscope. NFTs in particular grabbed Matthew's imagination. He realized this invention was "thing-ing the internet," as he puts it: making the ephemeral tangible. "It felt like a fruitful period — new technology, new stuff to play with," Matthew recalled.

Non-Fungible Tunes

As noted in Splits' recent profile of NFT trailblazers Transient Labs, "Decades of digital artists have pushed beyond analog limitations in the production and presentation of art, but before NFTs it was hard to package these innovations into something collectors could own." Zora cofounder Dee Goens wrote earlier this year:

Bringing things onchain reveals the economic demand for those objects and/or goods. When minting media, the exercise of minting reveals the economic demand for media across the internet that has otherwise been tucked away behind the walls of corporations.

Naysayers will point out that anyone can right-click and copy-paste the file associated with an NFT. Yoink, that's my jpeg now! Despite its superficial accuracy, this criticism is a red herring. The scarce artifact is not the file, per se, but the onchain object that includes it.

A token is a talisman — a condensed moment that can be carried forward into the future. So is a song. Matthew noticed this commonality.

He pondered the conundrum of compelling music NFTs. Songs are experienced differently from visual art. The innate thingness of a picture is comparatively straightforward (Walter Benjamin notwithstanding). A song has its own thingness, to be sure, but it's hard to pin down — a song is not wholly contained by any given instance of itself. For example, a cover is still the same song, unlike the replication of a painting. Someone can lie about the provenance of a song, certainly, but there is no "forgery" when it comes to music.

Matthew wasn't immediately sure how to thingify songs into NFTs, but he wanted to figure it out. He started thinking about CDs, and mixtapes:

"It definitely came from the nostalgia of growing up burning CDs," he told Splits. "It also felt like CDs form a strong analogy for NFTs themselves — the token is acting like an onchain vessel for the art it contains. Similar to how CDs are containers for the data (music or other) that they store." Matthew cited David Rudnick's Tomb Series as further inspiration.

Beyond the purely artistic potential of NFTs, Matthew knew that musicians needed dynamic economic infrastructure that worked with the internet instead of against it. Crypto represented an intriguing laboratory. He was ready to start trying things.

Music and the New Internet

Matthew considers Songcamp to be part creative studio, part freeform collective (and… kind of a web3 record label, after all — but we'll get to that). You can glimpse Songcamp's more mature form in its moment of germination. In May 2021, Matthew wrote:

A week ago, 13 strangers made roughly $34,000 USD off the sale of 3 music NFTs.

This was the result of Songcamp Genesis — a group of 9 musicians, 2 visual artists, and 2 project operatives who came together to try something new on the Internet.

Matthew began things, like so many other crypto founders, with a joint and a Discord server:

I did something I like to do about once or twice a week: I smoked a little weed.

That, with the ideas swirling about in my head, led me to spinning up a little Discord server called “SONGCAMP”. I had no idea what it was about, save for the opening line that I threw up on the first channel:

This is a place for music and the new internet to crash into each other.

I sent off an invite to ~10 people.

The next day — in my clearer state of sobriety — I kicked myself for throwing an idea out into the world without much of it figured out at all.

Nevertheless, three days later Songcamp had its first call.

Four people showed up. One of them being my brother.

We spoke of music and web3 and it was fun and insightful. But no real plan came to light. I thought maybe this Discord server was a bit premature, and I considered cancelling the scheduled recurring call the following Monday.

Long story short, Matthew didn't cancel the call. It became Songcamp's weekly Heartbeat, a virtual gathering of the nascent community. "The first camp pretty much happened on those calls," Matthew reminisced. After a general conversation and project update, everyone but the camp participants would drop off, and they'd workshop the songs together. Over time, Heartbeat developed a close-knit group of regulars who shared their rough drafts and demos with each other. "A culture formed on this call," Matthew said.

Songcamp remixes a pre-existing tradition. A songwriting camp is what happens when a bunch of musicians get together to jam and come up with songs. Often these gatherings are organized and funded by record labels, sometimes to generate material for a specific artist.

In March 2012, the New Yorker published a feature called "The Song Machine" (later expanded into a book) discussing the music industry's reliance on assembling these ad hoc collectives of vocalists and producers with a knack for earworms. It's a fascinating behind-the-scenes read:

Most of the songs played on Top Forty radio are collaborations between producers like Stargate and "top line" writers like Ester Dean. The producers compose the chord progressions, program the beats, and arrange the "synths," or computer-made instrumental sounds; the top-liners come up with primary melodies, lyrics, and the all-important hooks, the ear-friendly musical phrases that lock you into the song. "It's not enough to have one hook anymore," Jay Brown, the president of Roc Nation, and Dean’s manager, told me recently. "You've got to have a hook in the intro, a hook in the pre-chorus, a hook in the chorus, and a hook in the bridge." The reason, he explained, is that "people on average give a song seven seconds on the radio before they change the channel, and you got to hook them."

Today Jay Brown would mention TikTok.

Stargate works with about twenty top-liners a year, and creates some eighty demos. These are sent out to A. & R. departments at record labels, to artists' managers, and, finally, to the artists, for approval. Around twenty-five of Stargate's songs end up on records each year.

Tor Hermansen, half of the producer duo Stargate, compared their music to "new flavors awaiting the right soft-drink or potato-chip maker to come along and incorporate them into a product." Doritos are tasty, but you don't always want an industrial-scale culinary experience, you know? The authenticity of a home-cooked meal is irreplaceable.

On her blog, songwriter Shelly Peiken reflected on the downsides of industry songwriting camps:

Lyrics and sections were often contributed in bits and pieces and I started noticing, upon hearing a final mix, that parts of my song were missing… replaced by a sound bite or a line from someone in another room. Or another city. Sometimes the song turned out to be about something completely different from the original idea.

Songcamp is different. The musicians run the process, and own the output. In his recap of Genesis, Matthew marveled:

Musicians often grow used to a world where we wait months or even years to receive any sort of revenue from our work, if at all. Here, we experienced a project that in the span of a few weeks went from nothing, to 3 songs and artwork created from scratch, to over $30,000 in value.

Songcamp's "About" page is also instructive:

Songwriting camps have the potential to unlock new levels of creativity, confidence and friendship amongst groups of talented musicians. They often allow artists to stretch into yet unseen realms of their own artistry, as they crash into fresh ideas and people in new and inspiring settings. But all too often, the beautiful artifacts of such an experience — the songs themselves — don't make it out into the world. They get stuck in the music industry. New internet technologies enabled by blockchains offer us novel sandboxes to play in when it comes to putting out music.

And:

We envision a future where musicians are able to plug in and out of pop-up collective identities, songwriting camps, and headless bands — adding their unique styles to these networks as they form. We see a world where internet-native rights, royalties and accreditation can flow as smoothly as the music itself.

After Genesis, Songcamp has birthed three more camps:

- Elektra, a sci-fi phantasmagoria;

- CHAOS, a 77-person "massive multiplayer band" that "created a collection of 48 songs, produced a generative visual art project, developed a custom smart contract, and designed an interactive web experience" (this time, Splits helped!);

- and the most recent, C4.

Compact Discography

Slightly reeling from the tentacular chaos of CHAOS, Matthew wanted to pare things back for the next camp. You can tell from the minimalist name: C4 simply stands for Camp 4.

He circled back to the metaphor of CDs, and the challenge of crafting a compelling music NFT. Matthew had made a lot of progress since he first started thinking about it, and he was ready to refine his ideas. It had become clear what Songcamp was for: the group used internet alchemy to make spontaneity durable — making songs into artifacts that captured the collaboration that originated them. Matthew wanted to push this effect even further.

Music "doesn't feel like a tangible product," he mused, "but we do hold items that contain music." As in, hold in your hands. Old-school records, tape decks, and CDs with their lovingly designed liner notes "have this physicality and tangibility to them." Matthew wanted to make NFTs inspired by that tactile nostalgia.

C4 participants broke into small groups to create five songs, ultimately an EP (which is available to stream on the music platform of your choice). Those songs are ingredients for NFT collectors to make their own mini mixtapes:

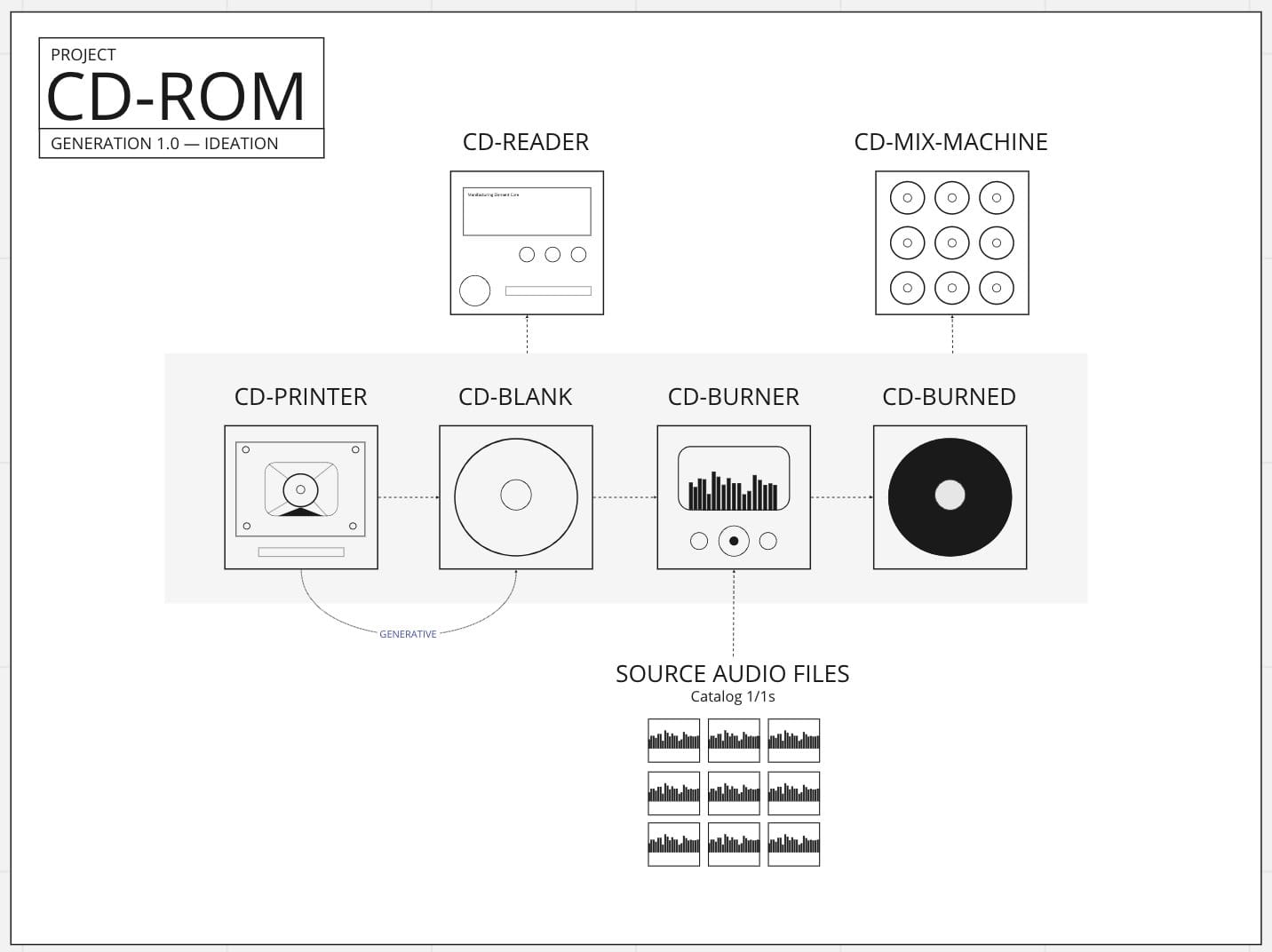

The main concept for the C4 collection and mint experience is to collect blank CDs and write/burn a song to those discs. Blank CDs each have the same artwork. They do not have any audio on them yet, and have enough memory to hold 1 song each.

Blank CD collectors then have the option to choose 1 of the 5 released songs to write to their disc. Writing to disc has 2 main consequences. The first is that it inscribes the chosen song onto the CD. The second is that the CD’s artwork evolves from the uniform blank design into a unique 1-of-1 generative artwork. Upon writing to disc, the user's song choice, token ID and wallet address are all used as input variables to create this generative artwork. We brought on creative coder reelaesthete to build out the CD generative art canvas.

You can peruse the mixtapes on OpenSea — note how few are available for sale. Collectors like to hang onto their Songcamp NFTs. The buyers are a combination of general web3 art appreciators and music NFT specialists like Noise DAO, not so much the hype-driven speculators. Matthew told Splits that more than 80% of day one CHAOS collectors are still holding their NFT, like a treasured concert T-shirt.

Songcamp x Splits

Songcamp uses Splits to automatically distribute revenue amongst all the contributors, as in the C4 Split:

"The way that you can use the economic piping and build out tools that are opinionated for musicians and collaborations between musicians" especially matters as Songcamp evolves into a broader platform. Matthew values the "ability to be creative beyond the music, the artwork, to extend that creativity down to the pipes."

Songcamp's goal is to "complement in a new way the existing label and publishing world that we live in," while "creating interesting legal and financial tools that allow musicians to work with each other, collaborate with each other, in a way that's transparent and fair."

Next Track

Currently Matthew is working on the fifth era of Songcamp. As with Transient Labs, he's thinking about how to scale the experiment. For CHAOS and C4, Songcamp built bespoke websites and custom contracts. "I got super hooked on that part, that dimension of the product was very exciting," Matthew said. Now he is "trying to build something a little less one-off, something foundational we can iterate on."

It's early days still, but what Matthew has in mind is software for musicians to manage releasing music together — "not collaborative Ableton, but the legal, the economic, and coordination aspects of musicians collaborating over the internet." After running Songcamp for a couple years, Matthew is intimately familiar with the logistical pain points.

In the meantime, the weekly Heartbeat call is on break so Matthew and his two full-time teammates can "focus our energy on the product design and build." He doesn't think it's a forever pause. "You could consider it on-season and off-season times," Matthew reflected. There's a natural ebb of activity between camps. "Inhale-exhale periods."

As for Matthew's own music career, he admits that Songcamp has "taken on most of my time." And increasingly it is a bit like he's running a record label. As the main organizer, Matthew has an active hand in curating the artists who participate, and Songcamp is designed to take songs from conception all the way to the finish line. As part of that, the music is not solely published via NFT, but now also on streaming, and the team handles that process for Songcamp projects.

The beauty of crypto-funded music is that "you're in complete control of your distribution" and "can be creative with it," Matthew said. Songcamp has kind of a yes-and mentality: the NFTs bring in the funding to support the musicians' work, which means they don't need to worry about measly streaming revenue (or lack thereof). They can make the music widely available for the sheer joy of sharing their art.

Songcamp x Splits v1

Back in June 2023, Splits did a quick Q&A with Russell Matthews, who leads the economics team at Songcamp. We spoke in the wake of Chaos, a headless band comprising 80 musicians, visual artists, engineers, writers, operatives + more. Over six weeks, Chaos released 21,000 music NFTs – each containing one of the 45 distinct songs plus a 1-of-a-kind cover artwork.

What problem does Chaos use Splits to solve?

In the music industry, revenue distribution has been opaque at best, and outright predatory at worst. Using Splits as our financial infrastructure has provided every participant absolute clarity surrounding their payments, with an ease of use that far surpasses the lengthy traditional finance process that would otherwise be our only option.

How has Chaos integrated Splits?

At Songcamp we've experimented with novel ways of musically collaborating en masse, integrating our split as the final destination for project proceeds. Splits allows each collaborator to individually manage the timing of when they get paid for both Songcamp projects, and any other personal projects that make use of Splits.

How has your experience been so far?

Our experience with both the Splits protocol, and the team working to expand its functionality, has been incredible. We’ve thrown previously non-existent use cases at the Splits team, and by adding 'modules' that layer onto the Splits protocol, they were able to support our technically challenging ideas!